.jpg)

This might be an appropriate time to vent some Jays angst that's been squeezed into a bitter little ball across the past few years.

Thankfully, we can do this without hitting any

ignorami with a whiskey bottle.

Joe Cowley got the reaming that

should be coming to anyone who judges an entire city, let alone a quote-unquote "Third World country," by what's available on his hotel room TV. At least he provided a prod to finish off a post that has been in the hopper since about 2008 (and as The Ack

noted, Cowley had little to say about Cleveland drawing about 5,000 less fans than the Jays did on both Friday and Saturday.)

Remember '08? The Toronto Blue Jays had the third-best run differential in the American League, but finished in fourth place in the AL East. Since most people make their judgment solely on won-loss records, this made their season a total fail to — appropriating the loose Cowleyian definition of

most — most minds. You might recall that in '08, the Chicago White Sox, the team Joe Cowley covers and

Ozzie Guillen manages, went to the playoffs after winning an AL Central tiebreaker over the Minnesota Twins. Those teams were a combined 1-13 against the Jays.

Going off on a rant at the time was ruled out — the whole whelp-of-a-beaten-cur thing. It did signal the Jays could no longer rate an emotional investment. It was,

Call me when there's realignment or balanced schedule. Call it a Captain Obvious statement, but it has hit the point where you need a schedule converter in baseball, similar to the "neutralize stats" function on

Baseball-Reference. As a fan born in 1977 who follows a team which has not made the playoffs since 1993, it would be nice to know how a contemporary team would fare in that 1977-93 era of two divisions and a balanced schedule, and vice-versa. The current setup obscures a team's true worth, which is an intolerable cruelty to visit upon fans.

In the '77-93 era, an American League club played every other team 12 or 13 times. That's a far cry from today's unbalanced sked (18-19 games vs. division opponents, 6-10 vs. other league foes, plus 18 interleague games). Now, there is a general understanding the calibre of competition in MLB varies between leagues and divisions.

People have known for years poor scheduling rigs the playoff races.

The popular understanding, though, seems to stop halfway. No one ever applies that 2010 knowledge

retroactively, like the characters in

Hot Tub Time Machine. It doesn't take

Keith Olbermann — although it was

gratifying he tweeted it — to know the Jays and Baltimore Orioles need a balanced schedule, or

realignment, as Paul Beeston has lobbied for. Some AL East widowers would tack on, "And a salary cap," although that sidetracks the argument.

The reality between the Jays then and now is not so polarized. The difference between the winnin' times in the 1980s and early '90s and also-ran Aughties are less than some might think. It's provable.

To hear people who only pay casual attention to baseball tell it, from 1985 to '93 Toronto simply had awesometacular teams and brilliant management. It is just apologist to point out the scheduling inequities that exist now — what about the 2008 Tampa Bay Rays? Never mind Rays owner Stu Sternberg also wants a balanced schedule.

Many are somewhat unaware of how the schedule is different than it was when Toronto had an annual contender, let alone its impact on a a team's record and its general perception. A 20-something sports consumer might be completely in the dark, like Clark Duke was about meeting women in 1986. Two divisions? Seattle and Boston each having to visit each other twice a year? That sounds ... exhausting.

However, examples abound that if the balanced schedule cleared a path for the Jays' success. Toronto's first playoff team in 1985 fared better vs. the AL West (55-29, .611 winning percentage) than it did vs. the East (44-33, .571). Manager Bobby Cox's boys took full advantage of having a near-equal opportunity to beat up on the bad clubs on each side, going 37-13 vs. the sixth- and seventh-place teams.

Or take 1989. The Jays won the division with a garden-variety 89-73 record. They went under .500 except when they got to beat on the two cellar dwellars, Detroit (11-2) and Chicago (11-1), graced by starting shortstop Ozzie Guillen on-basing a whole .270.

Perhaps lack of confidence stemming from not having the sabermetric chops to do it right, or worrying about not having the influence to make people listen inhibited writing about this in 2008. It kind of lay there dormant. Last week, though, Jonah Keri and Jeff Passan got into a little parry and thrust about the long-term outlook for those aforementioned Tampa Bay Rays.

Passan wrote a column about the Rays' pending loss of heart-and-soul leftfielder Carl Crawford that was pessimistic in outlook. Keri, who is writing a highly anticipated book about the inner workings of the Rays, was more pragmatic.

Keri touched on the realignment question, which one need not point out has been a hot topic since "floating realignment" was put forth as a trial balloon in a Sports Illustrated column."Why can't baseball get rid of its unbalanced schedule? Does it help MLB and its teams to have 18 games played between division rivals? Has anyone ever examined all the implications — on-field and off- — of this set-up? I’m not even necessarily advocating for it (we all love to see the Yankees and Red Sox spend 5 hours a night bludgeoning each other to death, 18 times a year, after all), I’m just asking."

It seemed like a fun exercise to try to retro-fit some the Jays' recent records into a balanced-schedule format, and guesstimate how some of their great teams would have fared with the unbalanced sked. Some problems creeped up, of course: - It's not so simple as sorting teams into their current or former divisions. For instance, in 1992, the Jays could have used 18 games against the Yankees. They went 11-2 against them. The Red Sox finished last.

In '89, the Kansas City Royals had the second-best record in the league. That sort of shoots down the idea of floating realignment, or realignment based on revenue. No one can know who will be good in 10 or 15 years.

- Won-loss records alone don't prove where a team ranks. Pythagorean W-L (run differential, essentially) is part of casual conversation. Next time you encounter a Jays fan, ask her/him which team had the best run differential in club history.

Chances are, the answer would be one of the World Series teams, or the '85 club. It was actually the 1987 team which lost the pennant to the Detroit Tigers on the final day of the season. You could look it up.

- Lack of math smarts. Someone much, much smarter would have to figure out how to control for how scheduling affects won-loss records and run differential, then rank teams. (In other words, don't read too much into the conclusions.)

- No interleague data. There is no way of knowing how the late '80s and early '90s Jays teams would have handled interleague play. The fact the '92-93 teams each won the World Series in six games (small sample size! small sample size!) doesn't mean each would have gone 12-6 in interleague play.

The Jays are an all-time 108-121 in interleague play. That .472 winning percentage works out to 8½ wins per 18 annual interleague games.

One half-assed way of going about it is to rank the Jays' opponents 1-13, making some adjustments based on run differential. For instance, in 1985, the Red Sox finished fifth in the East with an 81-81 record, but had the league's third-best run differential. (In hindsight, that makes their 1986 pennant seem lot less improbable that it was made out to be at the time.)

This is full-on admittedly simplistic, but the method is to take the 2008 team's record against each opponent and pro-rate each based on the earlier team's schedule. (For argument's sake, let's apply that 8½ interleague wins per season when modernizing an '85-93 team's record.)

Conversely, you can put the '85 or '92 Jays into the context of 2008, when Toronto played 63 games against the top four teams in the league, 11-15 more than they would have with a balanced schedule.

In '08, the AL was grouped thusly:East: 2, 3, 4, 12;

Central: 5, 6, 7, 10, 11;

West: 1, 8, 9, 13

In 2008, the Jays won three of nine games against the league's top team, the L.A. Angels, and seven out of 18 against the second-best, Tampa Bay. In 1992, they placed 12 games apiece against the Nos. 1 and 2 teams, the Oakland Athletics and Minnesota Twins. So the 2008 team gets half-ass pro-rated to four wins in 12 tries against the Angels, 4.666666 in 12 vs. Tampa Bay, and on down the line.

Conversely, that '92 team which went 5-8 against the Milwaukee Brewers would play them 18 times. It's all spread-sheeted, but here are a few of the results:'08 Jays, with the '92 schedule: 91.09 wins (actual wins: 86)

'92 Jays, with the '08 schedule: 91.66 wins (actual wins: 96)

'08, with '89 schedule: 90.56 (actual: 86)

'89, with '08 schedule: 87.5 (actual: 89)

'85, with '08 schedule: 92.6 (actual: 99, in 161 games)

'08, with '85 schedule: 91.27 (actual: 86)

'08, with '91 schedule: 91.43 (actual: 86)

'91, with '08 schedule: 85.8 (actual: 91)

The 2008 team ends up with 90.1 wins when teams are simply put back into two divisions. (By the same method, the 2006 club had 87.6, not far off its actual total. They'd still have to bust ass to earn it, the way it should be.)

By no means is this a claim any recent Jays club was as good as the fondly remembered teams which went to the playoffs and World Series. The point is to show how much the unbalanced schedule has messed with our heads. The first-place 1991 Jays and fourth-place '08 Jays practically end up trading records.

With the old balanced schedule and no interleague play, the '08 club would have at least had a puncher's chance at winning 90 games, having one of the top four records in the league, and being in a playoff race.

In most seasons, the AL has four 90-win teams.

That shows why MLB should go back to two divisions in each league, with two wild-card teams. It would increase the chances of the four best in the league making the playoffs and prevent the deck from being stacked against teams due to geography.

What's so wrong with that idea? (Better yet, get rid of the divisions in each league and have the top four teams advance to the playoffs, the same way the top four finishers in the English Premier League play in the Champions League the following season.)

No one could say with certainty how this would affect the Jays off and on the field, but one can imagine there would not be this hard crust of cynicism like the one that has formed around the franchise.

Perhaps they would even have enough momentum at the corporate level to justify building a real ballpark, like the new one in Minnesota, or the ones in northern cities such as Milwaukee and Seattle, whose teams have never won one World Series, let alone two. At the very least, FAN 590 callers would be able to "unbind their panties" (Mike Wilner, FAN 590) when there is an early-season crowd of 10,000.

(About that: It was the first two nights of the Stanley Cup playoffs, the Toronto Raptors had a must-win game the first night, Toronto FC had its home opener the second night, and have you noticed what happened to the global economy? The Jays aren't going the way of the Expos, since there is nowhere to go. Relocating the Oakland Athletics is more of a priority for MLB.)

Perhaps this is getting into Ken Dryden territory, where the golden age of sport is whatever it was like when you were 12 years old. However, following the Jays came about thanks to their proximity to Kingston, and their success in those days. Watching the franchise try to push the boulder up the mountain has taken that away.

Going back to the old schedule would not address revenue disparities. It would remain a related issue. Through all of this, there is an awareness baseball's excessive focus on big-market teams has not hurt its equity. It has gone from a $1-billion-per-year industry in the early 1990s to about $7 billion. Small wonder it can abide having about a third of its franchises busted down to being an outlet mall. You grimly walk in to Rogers Centre, get what you need (a baseball fix) and file out without being repaired emotionally or spiritually.

(As an aside, in all those then-and-now Blue Jays comparisons the media likes to make, no one seems to acknowledge how much the business of baseball has changed. The Jays' success coincided with a period when the Red Sox and Yankees each had ineffectual management, the former thanks to the wrangling over the Yawkey Trust and the latter due to George Steinbrenner was batshit insane.)

However, the Yankees and Red Sox could pass the division title and the first wild-card berth back and forth for the next 40 years for all I care, so long as it was possible to have three AL East teams make the playoffs.

Eliminating that unnecessary third division leaves a playoff berth that would still be there for the Jays, Baltimore Orioles, Kansas City Royals and yes, the Tampa Bay Rays. Beyond that, post-season baseball is a crapshoot. A short series in any sport offers a chance for a team make up for inequities in revenue or scheduling, à la the eighth-seeded Edmonton Oilers eliminating the No. 1 seed Detroit Red Wings in the first round of the Stanley Cup playoffs in 2006.

Until that happens, Toronto is deprived of having real baseball. Continuing to follow it makes me a total hypocrite.

Until that happens, Toronto is deprived of having real baseball. Continuing to follow it makes me a total hypocrite.

Please do not judge. Resenting a professional sports league yet still obsessing over it is what a simple kind of man must do to trick people into thinking he's "so motherfucking complex it's ridiculous." (Assist to fellow redheaded Kingtonian Jay Pinkerton.) Plus following a ballclub day in, day out, helps frame in that little world one lives in when he's too scared to change.

Obviously, no one gets to stay in the same world they knew when they were younger. Hopefully this shows why it's hard to believe in the Jays until they get to rockin' the same schedule they had when leg warmers, cassette players, George Bell's Jheri curl and V-neck jersey were popular.

A trip back to 1986 scheduling-wise might restore hope, just like it did for the guys in Hot Tub Time Machine.

Please excuse the forced reference to a popular movie. It just seemed like the best way to let Joe Cowley to know that Canada finally got its first movie theatre.

Roy Halladay as a No. 3 starter? The all-time Blue Jays, for a franchise that only began play in 1977, have a pretty deep pitching staff even without a certain federally indicted former right-hander.

Roy Halladay as a No. 3 starter? The all-time Blue Jays, for a franchise that only began play in 1977, have a pretty deep pitching staff even without a certain federally indicted former right-hander.

.jpg)

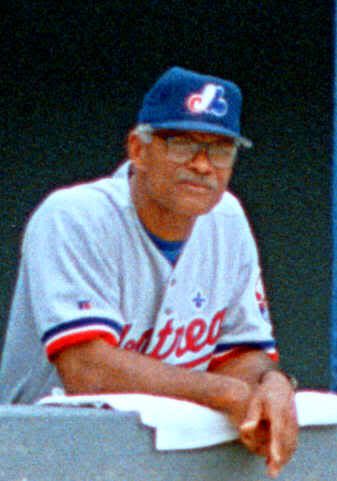

Thanks to Chris Jaffe, you might never look at the men in the dugout the same way.

Thanks to Chris Jaffe, you might never look at the men in the dugout the same way. As a 30-something Jays fan, Jaffe's method really hit home with the section on Jimy Williams, who managed Toronto from 1986-89. The next time you're talking to a serious baseball nut, ask her/him what manager in recent history got the most from the bullpen. One response might be, "Probably

As a 30-something Jays fan, Jaffe's method really hit home with the section on Jimy Williams, who managed Toronto from 1986-89. The next time you're talking to a serious baseball nut, ask her/him what manager in recent history got the most from the bullpen. One response might be, "Probably